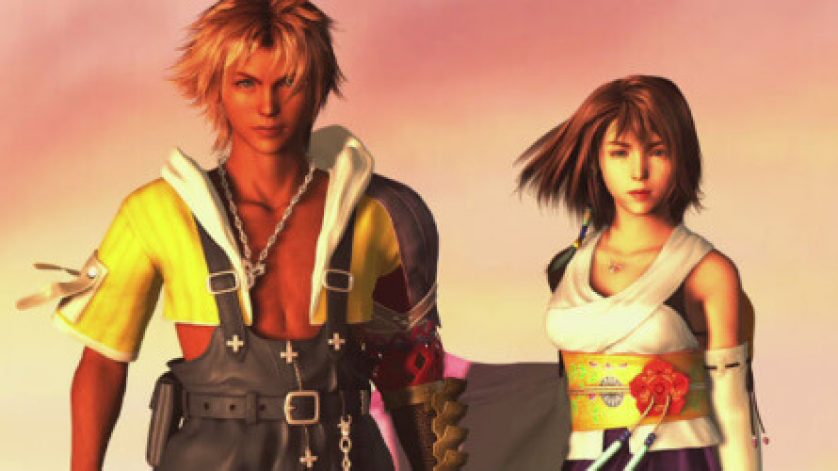

I think it’s no big reveal to say that Final Fantasy X dealt with a lot of sensitive issues: racism, class warfare, the corruption of organized religion, and the ethics of making your player dodge 200 lightning bolts in a row for an Ultimate Weapon component.

As such, I think most people are already on board with the idea that Final Fantasy X is less a story about fighting a singular bad guy than it is about changing a corrupt society. All the same, I feel it is worth delving into the details, as studying how this story handles this classic conflict can help us appreciate its message all the more. We may even get a glimpse into how it has affected the more modern Final Fantasy games.

First let’s take a look at the four basic literary conflicts: Man vs. Man, Man vs. Society, Man vs. Self and Man vs. Nature. Most stories fall into one of these four basic categories. As a simple refresher the conflicts work as such:

- Man vs. Man: Your standard Hero vs. Villain or Protagonist vs. Antagonist. The plot centers around the protagonist’s struggle to defeat or overcome a direct adversary. A literary example would be William Shakespeare’s Hamlet.

- Man vs. Society: The protagonist vs the world in which he/she lives. Rather than a central villain, the emphasis is how the society as a whole is adversarial. A literary example would be Victor Hugo’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame.

- Man vs. Self: The protagonist vs himself. A battle of identity, personal demons, or something of the sort. A literary example would be Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol.

- Man vs. Nature: The protagonist must overcome the wild or a natural disaster of some sort; a tale of survival. A literary example would be Ernest Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea.

The Good, The Bad and the Ugly

Given these descriptions I believe you can see how FFX exists as a prime example of Man vs. Society. “But Jason!” I hear some of you exclaim. “Final Fantasy X has a bad guy! Several in fact!” Okay, good point. But it is important to note that stories can (and frequently do) incorporate many or even all of these archetypes in their story. Just because a story is Man vs. Society doesn’t mean there aren’t singular antagonists. However, these antagonists are almost always framed as a product of the society that bore them. With that in mind, let’s take a look at our antagonists.

First and foremost is Yu Yevon, the architect of Sin and the focus of the world’s central religion. I don’t think I need to explain that one. By the same token Sin itself – as a creation of Yu Yevon – exists as a constant beacon around which society is run. Cities are built with constant Sin attacks in mind. Summoners give their lives with alarming regularity in order to buy a few short years of relief. The greatest non-ordained organization on the globe exists solely for the purpose of defending the people from Sin.

Then there is Seymour, a Maester of Yevon and arguably the chief “Bad Guy”. He is a person who holds a great deal of religious and political power. More importantly, however, is his personal backstory – one that was shaped by the society in which he (and everyone on Spira) lives. He lost his mother at an early age to the battle against Sin, with her becoming a Final Aeon – an ultimate summon used to defeat Sin. Repulsed by what she had become, he grew obsessed with the idea of protecting the world from death. His desire to die and become the next Sin stems from a passion to destroy the world out of sheer nihilism.

Finally you have Jecht, who might not at first seem to be directly influenced by the society of Spira. He – like Tidus – is an outsider in this world, but it is precisely his role to be the outsider that succumbs to the corruption of the society. In his effort to “rid the world of Sin” by volunteering to be Braska’s Final Aeon, he metaphorically surrenders his will to the system that has failed time and time again. You know what they say about the “road to Hell”; with the best of intentions he perpetuated a cycle that didn’t work.

There are other comparatively minor antagonists as well: Yunalesca, Yuna’s rival summoners, Biran and Yenke, and those jerks on the Luca Goers. However not one of them is simply evil just for the sake of being evil. Most of the ones I just mentioned aren’t even really evil, just kind of jerks. And Yunalesca doesn’t attack your party out of villainy but out of a misguided attempt to protect a system that she believes works as best as it can.

The Emphasis On Empathy

At this point I can hear you all going “So what? What is the point of all this?” Well patience, my dear reader, and I will tell you how this story is a sign that Final Fantasy’s story-telling is evolving. Because rather than this being a story of some heroes going out to save the world, this is a story of some heroes going out to change the world.

When we play Final Fantasy VI, exceedingly few of us will be able to identify with the struggle of having to match blades with an earth-shattering totem of unspeakable malignity. But most of us can identify with the struggles of the characters. If you’ve lost a loved one, Cyan’s story will speak to you. If you’ve ever felt ostracized for a mistake you made in your past, then you may be able to relate to Celes. Gau will speak to anybody who has ever been so hungry they literally ate dried meat from the first person to toss them some (in short anybody who has ever eaten at McDonalds).

Final Fantasy X adds a new level to that by making the story one on a larger scale. You may identify with the individual characters, but you can also now relate to the larger societal issues. Perhaps you can identify with the racism against the Al Bhed. Perhaps you have a mistrust for organized religion. Perhaps you feel like an outsider in a world that becomes scarier the more you learn about it – like an American who just binge-watched Last Week Tonight. We are seeing the series make this shift away from the traditional bad guy. They are instead becoming cautionary tales about society.

Final Fantasy XIII serves as a perfect example of this. It’s a society that has become so paranoid of the relatively unknown entity of Gran Pulse that it is more than willing to kill anybody who has come into contact with it. There is a scene in one of the early chapters with a “televised poll” showing overwhelming support for performing a similar Purge if one was needed. Apart from coincidentally sharing the name of one of the most mediocre horror films of the modern day, this scene of hasty “out of sight, out of mind” decision-making is something we see an awful lot of.

Fear dictates their actions because they have been bred to think like this. In Final Fantasy X the people who hated the Al Bhed were racist not because of a personal fault, but because their society had banged into their heads from a young age that these people were responsible for everything wrong. Now tell me honestly that you can’t see a bit of that in how racism works in this day and age.

Conclusion

Unfortunately, it goes beyond racism. The very idea of a governmental body that controls our destinies in ways we can’t really foresee goes back as far as Final Fantasy VII. Sure, most of us won’t be crushed like a bug under a falling plate. Though many of us know what it is like to be brought up taught that our government, our leaders, and the people in charge of us just want what is best for all of us. Then, as we grow older, we learn that they are merely continuing an imperfect system that suits them well enough. If they do care about the little man, they are ultimately powerless to do anything for them.

That is why stories like this are important. Stories that call attention to the problems we face everyday have been relevant in every era. Take my literary example of a Man vs. Society story. The Hunchback of Notre Dame was not a cute story about an ugly duckling and singing gargoyles with the voice of George Costanza. It was a damning skewer piece about the corruption of the Catholic Church and the society that allowed it to exist.

Unfortunately, only in a fantasy do the problems of society go away by slaying the final boss. In fact one of the few things I’ll give credit to Final Fantasy X-2 for is that it explained that some people have a hard time letting go of the old ways and seek to rationalize large issues and isolated incidents. It’s not my intention with this article to bum you out, dear reader, but to show why it matters that we are seeing Final Fantasy move away from the classic story. Moral grey areas have always been a part of their story-telling, but now we are seeing them evolve into a more global message.

In the end, we don’t need a sword to be Tidus. We don’t need a staff to be Yuna. All we need to impact our world for the better is ourselves and the willingness to take action. That is the lesson we can learn from Final Fantasy X.

The author would like to thank Flintlock and The Blue Bandit who helped edit the article.

No comments yet

Log in or Register

No comments yet

Be the one to start the conversation!