Observations about the translation and localization of FFXV

With every Final Fantasy to see an English release, some names or terms are changed in the localization process. Sometimes this is arguably for the better: FFVI’s Terra, along with FFX’s Auron and FFXII’s Balthier, benefitted in this fan’s opinion. “Tina,” “Aaron” and “Balflear”? No thanks.

Other times we’re left with head scratchers (look for a couple of those below). Whether good, bad or not really that important, though, they’re coming. They’re going to happen. Final Fantasy XV is no exception.

In this section, we’ll look at some significant cases where the English localization team made changes from the Japanese version of the game.

Cindy’s name

For whatever reason, the first name of Hammerhead’s star mechanic, Cidney Aurum (written シドニー・オールム in Japanese), was localized to “Cindy” for the official English localization — despite “シドニー” being how even the name of Sydney, Australia is spelled in Japanese. This somewhat (annoyingly) obscures the fact that FFXV actually has two Cids.

Ezma’s name

Ezma, the leader of Meldacio’s Hunters, is named “Izania” (イザニア) in Japanese. As with Cindy above, this odd choice in localization obscures something more significant than just the name alone — though in Ezma’s case, it’s arguably much more significant, as a subplot involving her and her family serves as a direct parallel with the story of Ardyn and Noctis’s family (see “Izunia and Izania” under the “Fan theories about Ardyn” page).

The Astrals/The Hexatheon

Throughout the majority of the Final Fantasy series, summons have been referred to as almost literally that in Japanese: they’re called “召喚獣,” meaning “summon beasts.” FFVIII’s Guardian Forces actually were called “Guardian Forces” even in Japanese, but the rest of the creative names for summons seen in the English localizations of FFIX (Eidolons), X (Aeons), XII (Espers), and XIII (Eidolons again) were just “summon beasts” in Japanese.

In FFXV, the Astrals/the Six/the Hexatheon are something different — though still different from what we would see in the official English localization. Here, they are 神々(“the gods”) or 六神 (“the six gods”), though the command 召喚 (“summon”) still appears when calling them during battle. The reference to them as “the Hexatheon” in the Book of Cosmogony is also just “the six gods,” though this was undeniably a creative and cool term to refer to them by.

As one might realize upon learning this, the utter absence of the word “astral” in reference to the gods in the original Japanese calls into question a number of other uses of the word within the English localization and associated media — for example, the Tokyo Game Show trailer from 2014 that saw, in its official dubs and subs from Square Enix, the meteor outside Lestallum referred to as an “astral shard”:

• English dub

• Japanese audio with English subtitles

• English audio with Spanish subtitles (official Square Enix Spain YouTube channel); here, “astral shard” becomes “fragmento astral,” which means the same thing

• Japanese audio only

In Japanese, Ignis’s response to Prompto was simply “神話の時代の隕石だ”/Shinwa no jidai no inseki da — “It’s a meteorite from an era of myth.”

Despite this use of “astral shard” for the translation in the trailer, the similarly worded 神話の隕石/”shinwa no inseki” is what Ignis refers to the object as at the start of the “Pilgrimage” subquest (English name; in Japanese: “聖地巡礼,” meaning “Pilgrimage to Sacred Places”) if the player has Noctis agree to go see the Disc of Cauthess during Chapter 3, before the story actually requires one to go there. Unlike the dubbed and subbed TGS 2014 trailer, this scene in the English localization of the final game sees Ignis refer to the site with a more straightforward translation: “the Meteor of legend.”

Ironically enough, however, another nugget of optional dialogue in the English version of the final game sees Ignis once again refer to the Meteor as “the astral shard”:

Gladiolus: Yeah, I was just thinking the same thing.

Ignis: The rise in temperature is likely attributable to the astral shard. We’re close.

In Japanese, this reference to the space desbris was simply “隕石” — “the Meteor” (see 2:15 to 2:25 in this gameplay video).

Yet another notable “astral” change to come with the English localization is the subquest for Vyv called “Aftermath of the Astral War” in English. This subquest was named “神代の魔大戦” in Japanese. 神代 is “age of the gods,” and 魔大戦 is what the English localization calls “the Great War of Old” (it’s literally “Magic Great War,” the same name as the war from FFVI called the “War of the Magi” in the English localization) — so maybe think of the subequest’s name as something like “Great War of Old in the Age of the Gods,” or perhaps “Great Magic War in the Age of the Gods.”

An additional use of the word not present in the original script comes from Gentiana during Chapter 9: “Ahead lies a future uncertain, yet sure is the astral memory, wherein the King may walk.” Whether the localization team actually intended this particular occasion to reference the gods is unclear, but the Japanese sentence most certainly didn’t — and it even more certainly didn’t include the word “astral” (for reference, see 14:51 in this video):

時を戻すことを望むなら叶えましょう

________________

“In preparation for the unforgiving struggle ahead — let it be granted if you wish to turn back time.”

Before we close out this study, for good measure, there is one more use of “astral” players of Final Fantasy XV see a lot of that actually does not include the word: the Astralsphere. This was entitled “アビリティコール” (“Ability Call”) in Japanese.

Magitek

The Japanese term “魔導,” localized as “magitek” for the English versions of Final Fantasy VI and Final Fantasy XV, simply means “sorcery.” Generic though that sounds, it’s actually less generic than “魔法,” the word meaning “magic” generally used in Final Fantasy for that purpose — and when “魔導” does appear in the FF series (e.g. FFXIV: A Realm Reborn and FF Type-0), it’s applied to concepts that clearly reference those it shares its name with from FFVI.

As for the word “magitek” itself, it appears to be just a clever portmanteau of the words “magic” and “technology.”

Inconsistent loading screens about Ifrit from “Episode Gladiolus”

When “Episode Gladiolus” was released at the end of March 2017, it featured a loading screen that seemingly confirmed a theory many fans had held since the game’s release close to five full months earlier:

A bizarre discrepancy was soon discovered, however. This information about Ifrit’s original body being at Ravatogh was not present in the loading screen for all regions who received the DLC. While the English, German and Portuguese versions of the loading screen do contain this statement, the Japanese, French, Italian and Spanish versions do not:

The precise cause and/or meaning of all this is unclear at the moment, but it has been proposed that these localizations may have been written in parallel yet not in collaboration, leading to some localization teams getting additional information that was added closer to release after an initial transfer of information, while other teams either didn’t receive it or didn’t act to add it in before release.

It has also been suggested that some details were added to the English version that either didn’t get added to the Japanese version before various other localizations were made based off thsee two — or that the updated Japanese file was simply overlooked with the outdated file added back in to whatever data transfer was sent to the French, Italian and Spanish localization teams.

Of course, the most pressing question here is this: As a fan, what to do with this conundrum? For the time being, this fan will assume the information about Ifrit’s body being at Ravatogh is canon.

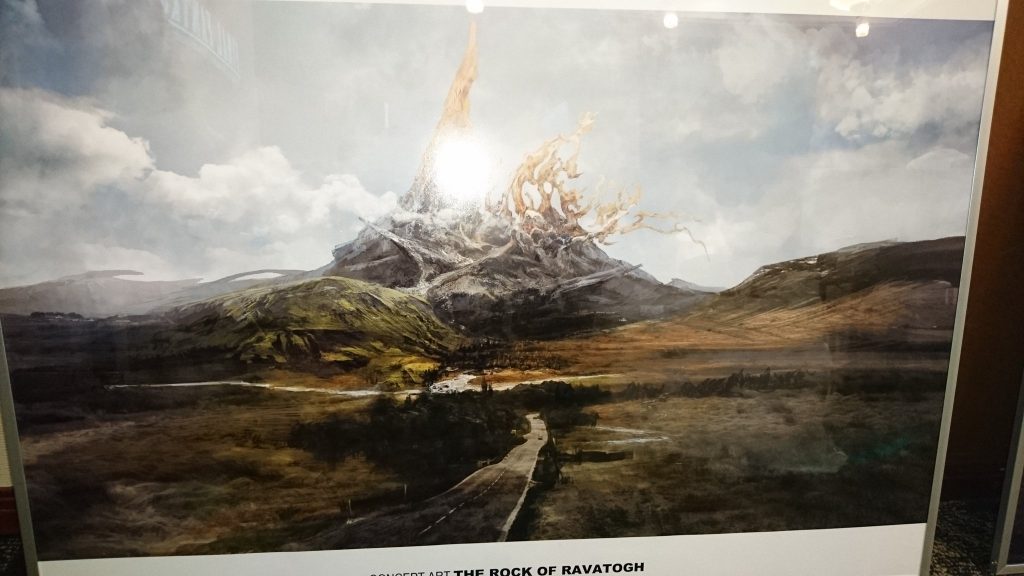

The design of the unique formation atop the volcano is obviously that of Ifrit’s horns, whether looking at the concept art for the Rock of Ravatogh or its in-game design, whether comparing Ifrit’s horns while adorned with fire or without. They may not be exact, but they are there. They just simply are.

Speaking of fire, its relevance when talking about Ifrit should require no more explanation than the environment of the Ghorovas Rift when talking about Shiva.

Looking now from designs back to the loading screen text in question, not only is that quite a large chunk of text to plausibly “slip in” without it belonging, it’s also a rather large chunk that isn’t actively contradicting anything in the Japanese version. Were it the case that the Japanese release offered an account incompatible with the English one, we would almost certainly have to dismiss the latter. Yet with the matter being as it is; with the possibility that other localization teams simply worked from the English and Japanese data; and with the ever present possibility that a similarly named file was simply overlooked or mistakenly selected for transfer from among a lot of other data — it seems most prudent to simply incorporate this information into the established lore.

It had to come from somewhere, and though the English localization team has certainly demonstrated some creative liberties here and there, this would amount to outright fabricating something that could — for all they know — end up contradicted by a new story segment to be added later. It’s difficult to imagine them being quite so foolish, even if not impossible.

Even were they tempted to throw it in there as a nod to theories from fans, they must also be aware of the avid translation efforts going on in the fan community. One can’t picture these industry professionals expecting such a move would be well received.

Maybe someone did make a foolish call, but for now, this fan is going to go with assuming the best of them.

Final Fantasy XV’s Version 1.16 update of September 29, 2017 provided visual confirmation of Ifrit’s body having indeed been at Ravatogh. When Shiva’s narration gets to Ifrit being resurrected and corrupted by the Starscourge, we are shown imagery of Ifrit rising to his feet at what is clearly the Rock of Ravatogh.

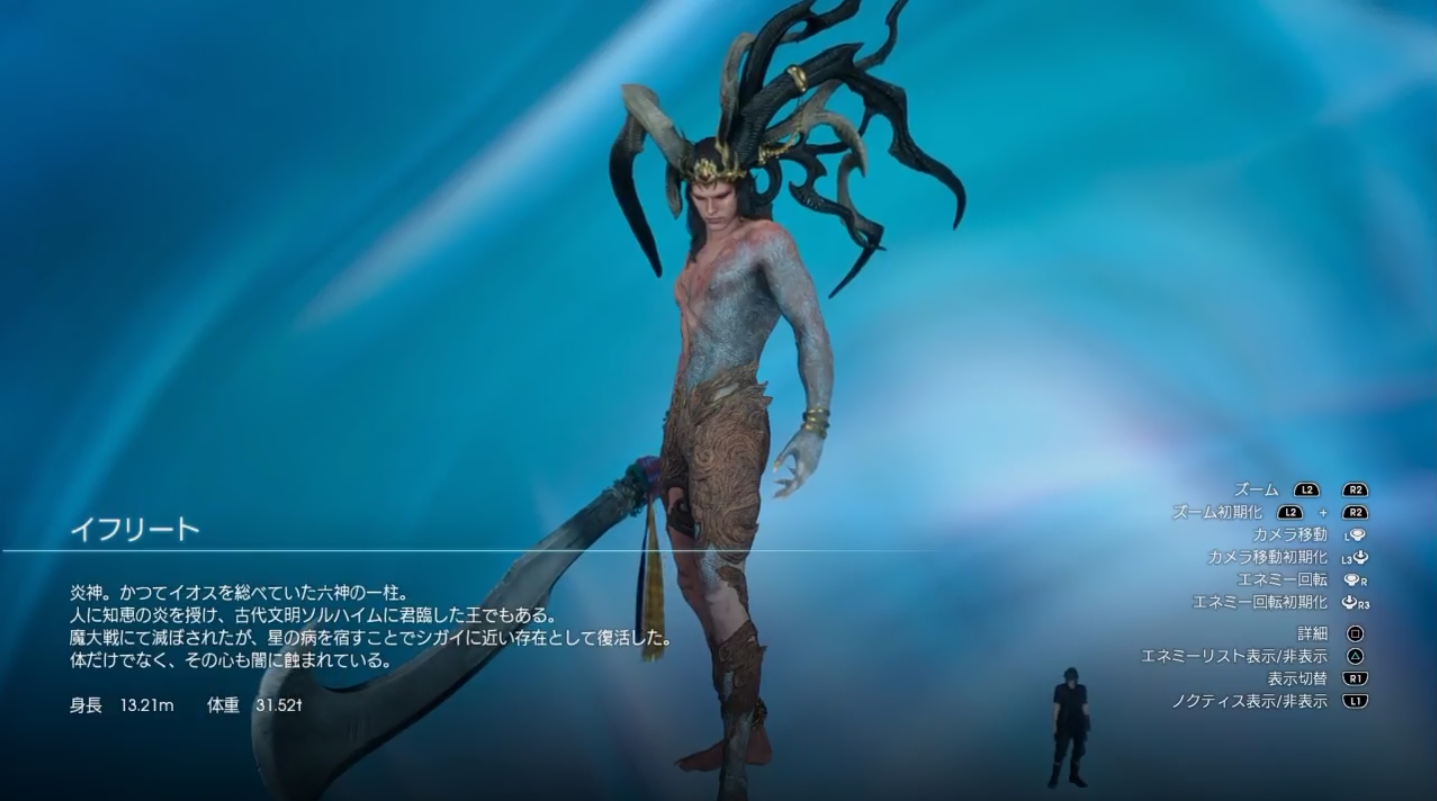

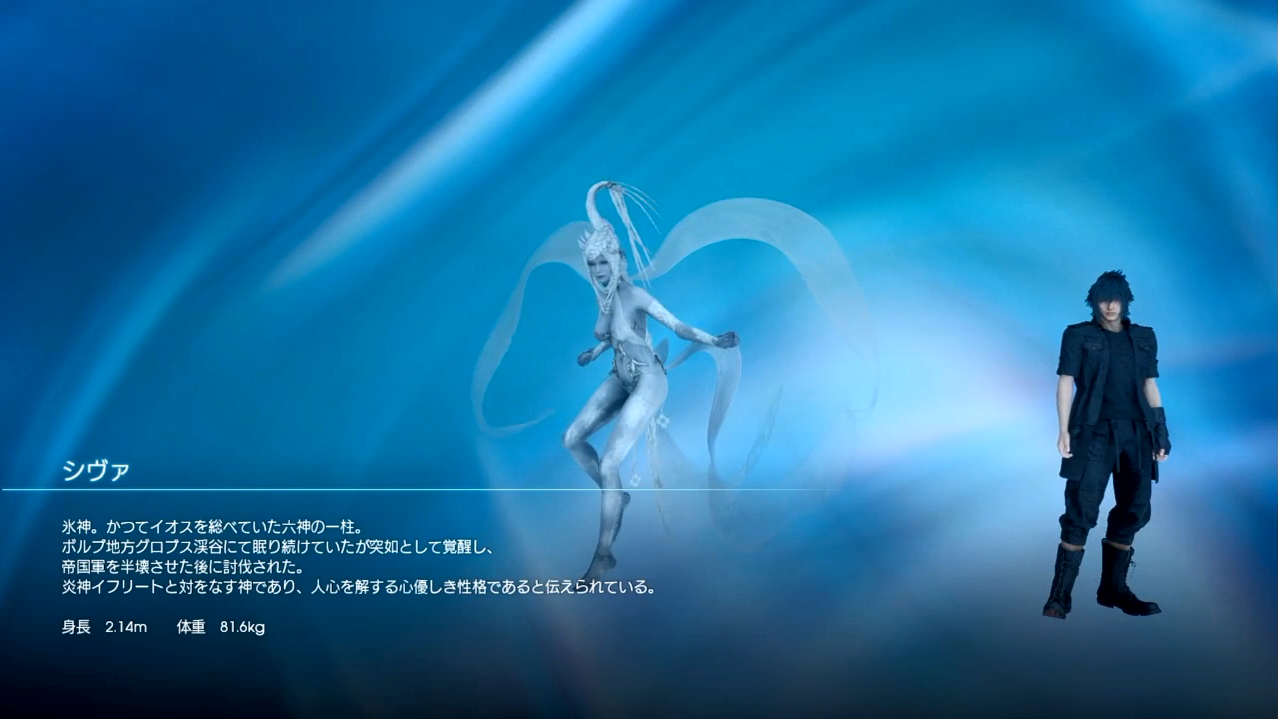

Inconsistent bestiary entries

The Version 1.15 update to FFXV on August 30th, 2017 brought with it two primary new features in the form of the “Assassin’s Festival” event and a long-awaited in-game bestiary. As with the loading screen from “Episode Gladiolus” detailed above, discrepancies between different languages’ versions were soon recognized — in particular, the bestiary entries for Ifrit and Shiva seemed to paint different pictures of occasional significance between the original Japanese text and official localizations.

We will observe these differences below by listing the English localization of the two gods’ bestiary entries followed by the German localization (with a Google-assisted translation of that text into English), and then follow that up with the Japanese text (along with this author’s own translation).

Der Gott des Feuers. Eins wachte er als Teil der göttlichen Sechs über Eos. Er liebte die Menschen und schürte ihren Wissensdurst. Auf diese Weise verhalf er der Zivilisation Solheims zu großer Blüte. Doch trunken vor ihrer Macht wandten sich die Menschen gegen die Götter. Im darauf entflammenden Astralkrieg wurde Ifrit bezwungen und wurde später mit dem Siecher-Parasiten infiziert. Nicht nur äusserlich, sondern innerlich ist er seither von der Dunkelheit zerfressen.

The god of fire. Once, as part of the divine six, he watched over Eos. He loved mankind and stoked their knowledge. In this way, he helped Solheim’s cilivization to flourish. Drunk with power, however, man turned against the gods. In the Astral War that followed, Ifrit was destroyed and later infected with the Starscourge. He has been consumed by the darkness not only externally, but internally as well.

人に知恵の炎を授け、古代文明ソルハイムに君臨した王でもある。

魔大戦にて滅ぼされたが、星の病を宿すことでシガイに近い存在として復活した。

体だけでなく、その心も闇に蝕まれている。

He also reigned as king in the ancient civilization of Solheim, and bestowed upon humanity the flame of wisdom.

He was destroyed during the Great War of Old, but was resurrected as a daemon thanks to the Starscourge.

Not only his body, but also his mind have been eroded by darkness.

Sie ruhte in der Ghorovas-Schlucht in Vogilupe, wo sie plötzlich erwachte und die halben Streitkräfte Niflheims auslöschte, bis diese ihr schließlich Herr werden konnten. Sie war die Geliebte von Ifrit, bis dieser seinem Wahn verfiel, und gilt als verständnisvoll und den Menschen wohlgesinnt.

The goddess of ice. Once, as part of the divine six, she watched over Eos. She rested in the Ghorovas Rift in Vogliupe, where she suddenly woke up and wiped out half of Niflheim’s forces until they could finally overcome her. She was the lover of Ifrit until he fell victim to his madness, and is regarded as understanding and benevolent to man.

ボルプ地方グロブス渓谷にて眠り綾けていたが突如として覚醒し、

帝国軍を半壊させた後に討伐された。

炎神イフリートと対をなす神であり、人心を解する心優しき性格であると伝えられている。

While sleeping in the Vogliupe region’s Ghorovas Rift, she was suddenly awakened, and destroyed half the imperial army before being overwhelmed.

Legend says that she is the god who serves as the opposite counterpart to the fire god, Ifrit, and that she has a gentle personality, understanding of the human heart.

The drastic differences to be observed here include a claim from Ifrit’s German entry that that the people of Solheim rebelled against all the gods, while the English entry only mentions them betraying Ifrit (the Japanese entry meanwhile makes no mention of betrayal at all); the English entry’s claim that Ifrit gifted fire to mankind, while the Japanese and German entries speak more of an intellectual fire (Ifrit’s gift to man of literal fire would be confirmed, however, in the Version 1.16 update of September 29, 2017); and the German entry claiming that Shiva and Ifrit were lovers, while this doesn’t come up in the English and Japanese entries (their relation to one another would be confirmed, though, in the aforementioned Version 1.16 update).

Other notable differences in the bestiary include those entries for Bahamut and the daemon naglfar. We will turn now to these, examining first the official English localization’s take followed by the original Japanese text (yet again accompanied by my translations into English).

ルシス王家と最も関係が深い神であるといわれる。

炎神が滅び、古代文明を崩壊させた魔大戦の終結後、神々の中で唯一眠りに就かなかった。

真の王の目覚めを待ち、その使命の履行を望んでいる。

He is said to be the god with the deepest connection to the Lucian royal family.

Following the Great War of Old that destroyed the god of fire and decimated the ancient civilization, he was the only one among the gods not to sleep.

He awaits the True King’s awakening, and hopes to fulfill his mission.

外見の似ているデスクローと比べても、桁遙いの力と残忍さを備えている。

星創記の偽典にこの名が記されており、

ルシス黎明期に二十四使と相討ったとされ、その再来は『災厄』の前兆といわれている。

Compared to the similar looking Deathclaw, it possesses extraordinary power and brutality.

It is said that its name is recorded in pseudepigrapha of the Cosmogony,

that it did battle with the 24 Messengers during the dawn of Lucis, and that its return is said to be an omen of “calamity.”

Let us look first at Bahamut’s official English entry, as compared against the original Japanese. An enormous difference to be found here — one that would carry enormous implications for the timeline of the FFXV Universe were the English entry entirely correct — is the claim that Bahamut stayed awake while the other gods slept so as to await the arrival of the Chosen King. Were this accurate, it could refer only to Ardyn or Noctis, with the implication then being that the Starscourge spread during the Great War of Old, and possibly even that the key events of Ardyn’s prior existence as a human (absorbing the Starscourge parasite, becoming a daemon, being betrayed, etc.) occurred during the gods’ war.

What becomes clear when studying the Japanese entry, however, is that the last two sentences were combined into one for the English entry, and Bahamut’s activities from the last sentence linked to his decision to remain awake from the previous sentence. This decision on the part of the localization effort was made in error, however — unless they are aware of extremely important information about the lore of the FFXV Universe that has not yet been revealed to fans, and simply wrote the translation with that knowledge in mind. That, of course, is still a possibility at the time of this writing, which must be acknowledged. However, looking at the Japanese sentences themselves, they simply do not say what the localization said.

Furthermore, looking at the structure of the other gods’ bestiary entries — even the gods’ other entries written for the English localization — we find a pattern that isn’t reflected with the official English translation. Each entry introduces its designated god, provides some brief backstory on that god, and then gives information about them that occurred relatively close to the present day — even during the game in some instances. In the case of Ramuh, Titan and Leviathan, their entries move from introducing them to speaking of their slumber following the war of the gods, and then to Lunafreya awakening them. In Ifrit’s case, he’s introduced, his death is addressed, and then the relatively recent developments of his resurrection via the Starscourge and corruption by the same are recounted. Similarly, in Shiva’s case, we find the development in which she was killed in battle with Niflheim mentioned in her entry, both this event and Ifrit’s resurrection having taken place eleven years prior to the beginning of the main game (another detail confirmed by the Version 1.16 update).

It stands to reason, then, that the last information offered about Bahamut’s activities in his own entry would likely also apply to recent history — and indeed, Bahamut has clearly been awaiting Noctis’s arrival for some time prior to the young king meeting him late in the game. Could he have been waiting since the end of the Great War of Old? Sure, it’s still possible. There’s little reason to believe that to be the case, however, when it would be at odds with the structure of the other gods’ bestiary entries, and when the basis for such a conclusion is currently predicated solely on conflating two sentences that don’t appear to belong together.

Finally, we move now to the naglfar’s English entry, where we are told that the daemon is said to have fought the divine twenty-four Messengers in “lost pages” of the Cosmogony. Though this terminology may be applicable, what was actually said here carries far more ecclesiastic connotations. The Japanese term used here was 偽典, meaning “pseudepigrapha,” which might be used at the colloquial level as synonymous with the similar colloquial use of the term “apocrypha” (i.e. writings of dubious authenticity) or to mean something akin to “falsely attributed writings,” but which Merriam-Webster defines as “any of various pseudonymous or anonymous Jewish religious writings of the period 200 B.C. to A.D. 200; especially one of such writings (such as the ‘Psalms of Solomon’) not included in any canon of Biblical scripture.”

“Pseudepigrapha” carries more of a religious connotation than being a way of denoting simply that a work may have been written by someone other than who the work is attributed to (or who the author claims to be). Though indeed loosely related to the original religious use of “apocrypha” — with similar implications for its standing (neither such works are accepted in the organized Christian or Jewish canon) — and with the potential for overlap between the two, a key difference here is that religious apocrypha, at least in so far as the Judaeo-Christian tradition is concerned, is firmly established. There’s something of an established canon for the apocrypha; “a canon for the non-canon scriptures,” one might say. The category is unlikely to grow. Pseudepigrapha, on the other hand, certainly could, and are unlikely to even receive as much acknowledgement as being included in the “canon of the non-canon.”

That latter area is where we find the writings that speak of the naglfar battling the twenty-four Messengers. Said event may very well have still taken place, but whatever religious body or organization on Eos who qualified as the establishment to decide canonicity where the Cosmogony is concerned would not have recognized those documents as authentic or even worthy of remembrance.

“Blessed Stars of life and light…”

There are multiple references to “our star,” “the star” and the “blessed Stars” throughout the English script. None of these are actually referencing a star, however, either singular or plural.

The word translated as “star” in these instances is “星” (i.e. hoshi) in Japanese; the word used for celestial bodies in general. It can mean “star,” but can also refer to planets — and, indeed, is not only what everyone in FFVII refers to that game’s planet by, but also what FFXV’s Lore Guide from the game’s opening tutorial explains the word to mean in this game.

In the Japanese version of FFXV, the segment of the Lore Guide entitled “The Six and the Oracle” ends with an additional line that says ちなみに、これらの話題でいう「星」は「世界」の意です — “By the way, ‘star’ in these topics means ‘world.'” This either became “star” in the official English localization due to an error in translation or, as is more likely, a deliberate choice on the part of the localization to give some linguistic flair to the game’s dialogue.

Click here for a screenshot or here for a video showing this segment of the Lore Guide in the Japanese version.

“Ahh, the face you wore the day you—”

An unfortunate omission of the English localization is found in Chapter 12 when Shiva reveals herself to Ardyn and Noctis. The English script has Ardyn begin to comment on a past occasion when he apparently saw Shiva in Gentiana’s form. The ice goddess turns him to ice before he can finish his sentence, however, cutting him off.

In the Japanese script, it’s clear that Ardyn was referring to the day some eleven years earlier when Shiva died in battle with the empire:

“You also had that lovely face when you were killed—”

“… The mortals created in their image”

With the Version 1.16 update applied to Final Fantasy XV on September 29, 2017 came new scenes adding significant backstory to the setting via narration by the ice goddess, Shiva. While informative in any language, the English localization included several details not present in the Japanese text, furthering the misunderstandings between the two.

We will observe these differences below by listing the English localization of the three segments to Shiva’s narration followed by the original Japanese text along with this author’s own translation of the Japanese wording.

The Six have safeguarded this star since time immemorial—each of a different mind, but united by this common purpose.

The gods’ protection extends to all creatures here below—even to the mortals created in their image. They are feeble creatures leading fragile lives and clinging to foolish fancies. The Frostbearer scorns these visions of “hope” which melt like snow in the sun’s light.

Yet the Pyreburner admires their strength of will. For their reverence, he grants unto them his flame, and the world of man flourishes.

His benevolence warms the heart of the Frostbearer.

It is not long, however, before some among those men ascend to new heights of hubris. The people of Solheim spurn the gods who blessed them—the gods they once worshipped.

The ungrateful mortals incur the wrath of the Pyreburner. He seeks to raze the very civilization his flames once helped build.

But the Six are sworn to defend the star and all its inhabitants from harm—and, at times, from one another.

The flames of war surge as Solheim fends off the Pyreburner’s fire. The gods’ pleas for peace fall on deaf ears, and the battle rages on. When the smoke clears, the world of man is in ruins, their star left scarred for time eternal. Wearied from war, the Six seek solace in slumber.

This tale of our shared past is entrusted to the King of Kings…

…that he may see it to its conclusion.

His peril is sensed by the Frostbearer. She rushes to his aid, only to be felled by the foreign hordes.

Those masses are now one with the darkness—darkness that, before long, will swallow the Six and the star they protect.

This star’s fate no longer rests in the hands of the gods. It sits on the shoulders of the Chosen.

Deliver this world from darkness—and grant my love release.

When the boy begins his existence on this star, the girl is met by the High Messenger.

It is ordained that she will work with him to return the Light. The girl reaffirms that promise.

The High Messenger is moved by the girl’s determination, her heart warmed by the girl’s benevolence. Her faith in mankind is restored once more.

私たち六神は 星を守りし存在――

各々の意志をもって その使命を果たさんとしていた

かつて私は——数多の生命の中で『人』は星に心要無きものと考えていた

儚く 脆く それ故可能性や希望といった曖昧なものを信じる人が星にとって有要だとは思えなかった

イフリートは 私とは違い

人の可能性を信じ 火を与え 共に繁栄の道を選択した

私はそんな彼に惹かれ 愛し合うようになった

私は——彼が信じる人のを信じることにした

だが 人の文明 ソルハイムは高みに達し驕った人は 神を排斥しようとした

恩を忘れた人の行為はイフリートの逆鱗に触れ彼は人もろとも世界を焼き尽くそうとした

私は 彼と戦わねばならなかった

星と 彼が信じた『人』を守るために

人と六神同士の戦いは 熾烈を極めて神々の調停も虚しく 戦いの規模はさらに拡大した

この魔大戦と呼ばれ戦いにより ソルハイムは滅び星は傷つき 疲弊した神々は永き眠りについた

これが選ばれし王に託せし星の物語

そして——私の物語

イフリートは何者かによりシガイにされてしまった

眠りから覚めた私は 彼を解放しようとするも帝国に砕かれ 力を失った

今や 帝国はシガイとともにあり六神も世界も闇に覆われようとしている

もはや私たちだけでは イフリートは元より星を救うことも叶わない

彼にはせめて 安らかなる死を——

選ばれし王ノクティスが誕生し私は神凪であるルナフレーナに会った

彼女は あなたと共に星に光を取り戻すと約束した

彼女の温かく 力強く 人を愛する心にふれ私は 再び人を信じようと思った

We Six Gods exist to protect the planet—

Each of us working to fulfill that mission in our own way.

Once upon a time, I thought … the many “human” lives were unnecessary for the planet.

They are fleeting. They are fragile. Therefore, I couldn’t believe that the humans who believed in such ambiguous things as possibility and hope were necessary for the planet.

Ifrit was different from me.

Believing in the potential of humans, he chose to gift them with fire and prosper with them.

This drew me to him, and we came to love one another.

And I … decided to believe in the humans as he believed in them.

However, the people of the Solheim civilization reached great heights, and the haughty humans tried to cast out their god.

This action by the humans, who had forgotten his blessings, incited Ifrit’s wrath, and he tried to raze the world along with the humans.

I had to fight him.

To protect the planet and the “humans” he had believed in.

The battle between god and man was extremely violent, the efforts of the other gods to mediate were fruitless, and the scale of the conflict grew.

This battle that came to be called the Astral War destroyed Solheim, injured the planet, and left the utterly exhausted gods to sleep for an eternity.

This story of the planet is entrusted to the Chosen King.

And … so is my story.

Ifrit was turned into a daemon by someone.

I awoke from my sleep and tried to free him, but I was destroyed by the empire and lost power.

Now that the empire and daemons are together, the Six Gods and the world are about to be swallowed in darkness.

No longer can we save Ifrit and save the planet.

He can at least be at peace in death …

When Noctis, the Chosen King, was born, I met with Lunafreya, who would be Oracle.

She promised to restore light to the planet with you.

Her warm, powerful, compassionate heart made me feel faith in mankind once more.

Notable differences for us to take note of here include:

• Shiva saying that mortals were created in the gods’ image isn’t present in the Japanese script

• The “High Messenger” title Gentiana is referred to with in the English script isn’t used. Gentiana/Shiva just consistently refers to herself with 私/”watashi” (i.e. “I”) — which is actually something of a point of confusion all its own given, as it further blurs the lines about precisely to what extent Gentiana and Shiva are separate beings. They certainly were at one time, as Gentiana began living with the Fleuret family in the year 732 M.E. while Shiva was still asleep in the Ghorovas Rift. However, Shiva speaks with Gentiana’s voice in this scene (in English and Japanese), and consistently refers to herself with “watashi”/”I” while speaking to things both Gentiana and Shiva did. Perhaps both entities no longer see a distinction between themselves?

• The English script here reiterates what Ifrit’s German bestiary entry (discussed earlier in this section of the archive) said about the people of Solheim rebelling against all the gods rather than just Ifrit. However, the Japanese version of this newest material — as with Ifrit’s Japanese bestiary entry — makes it sound as though they rejected Ifrit specifically, saying だが 人の文明 ソルハイムは高みに達し驕った人は 神を排斥しようとした (“However, the people of the Solheim civilization reached great heights, and the haughty humans tried to cast out their god”), which contains “kami”/神 (singular) rather than “kamigami”/神々 (plural), even while the Japanese narration doesn’t otherwise hesitate to use the plural rendering on several other occasions

• Gentiana/Shiva actually uses Lunafreya’s name rather than just referring to her as “the Oracle,” “the girl” and “the lady”

• In Japanese, Shiva’s past contempt for humanity comes across much more strongly. It even appears, given her narration at the time the image is shown of humans freezing to death, that she may have killed many humans herself in the distant past

Ostracized, demonized and forbidden to ascend

When Ardyn reveals his true identity to Noctis near the end of Chapter 13, he delivers a monologue in which he briefly goes over his past and what made him into the man he is today:

While the localization of this speech is, indeed, elegant and pleasant to listen to — especially delivered by Ardyn’s voice actor, the fantastic Darin De Paul — it fails to fully convey an important detail.

In the original Japanese script for what Ardyn says here, he reveals that the one named Izunia who betrayed him not only made a pariah of him, but also either executed him personally or caused his execution. The line that became “But a jealous king, one not yet chosen by the Crystal, ostracized and demonized this healer of the people” in the official English localization was が、まだクリスタルに選ばれていなかった王はその 人々を救える 唯一の男を殺してしまった in Japanese.

A more direct translation of this would be “However, a king not yet chosen by the Crystal killed that only man who could save the people.”

Along similar lines, Bahamut’s explanation of “the Accursed” to Noctis shortly thereafter also lost some valuable information in its transition to English, as well as led to some confusion among English-speaking fans. When Bahamut describes Ardyn with “One so impure of body and soul was deemed unworthy of the Crystal’s Light, and forbidden to ascend,” by “ascend” he means “become king.” This turn of phrasing for the English localization, while elegant, is confusing, coming as it does right after “A man cursed with life eternal, whose immortality stems from the selfsame scourge that wrought the daemons.”

The reasonable implication to take from “deemed unworthy of the Crystal’s light, and forbidden to ascend” is that it ties directly to Ardyn becoming “cursed with life eternal.” In other words, that Ardyn cannot die and “ascend” because he became “one so impure of body and soul” that the Crystal rejects his soul returning to itself, the soul of the planet.

This understanding, while the reasonable conclusion to draw, is an unfortunate misunderstanding encouraged by the wording chosen here for the localization. What Bahamut actually says in Japanese is その汚れた身体を聖石に拒まれ王位に就くことなく葬られた愚かな男. A more direct translation of this would be “A foolish man who was rejected by the Holy Stone for that unclean body and was buried without ascending to the throne.”

Ardyn’s immortality, meanwhile, is a result of the Starscourge itself rather than due to the Crystal’s rejection of him for absorbing the Starscourge.